Scanning Machine Brains

How supervised probing can help us isolate linguistic understanding in LLMs.

I previously wrote about Automating UMR Aspect Annotation, where we tried a variety of methods to use neural networks to label linguistic aspect. Surprisingly, even massive LLMs like GPT-4o and DeepSeek R1 struggle with aspect labeling through prompting alone. So—do they actually “understand” aspect? To investigate this, I ran supervised probes for every hidden layer of BERT across a selection of token positions using a target dataset.

Why this matters. Linguistics should be inherently interesting, but I know not everyone feels that way. Still, probing LLMs is a great lens for anyone trying to understand what these models actually do. As AI becomes more widespread, the need for interpretability increases-not just for academic curiosity, but to evaluate risks, bias, and trustworthiness. Think of probing like putting an LLM into an MRI machine while it “thinks” about a concept. Which parts light up when it processes aspect? If we could identify these “neurons,” could we or influence the model’s behavior?

What is aspect and how do we probe for it?

The GraphSpect framework we’re trying to build relies on LLM embeddings as the base layer in the architecture, based on the hypothesis that LLMs have a decent enough representation of linguistic phenomena. We’ve already shown that LLMs struggle with labeling aspect categories (in fact LLMs may have poor meta-linguistc knowledge altogether), so if they don’t even capture aspect phenomena, then we’ll have to rethink our entire approach.

For the less linguistically-inclined, aspect has to do with how an action or event unfolds over time. Unlike tense, which deals with when the event happens, aspect represents things like the duration or boundedness of the event. When we discuss the aspect of an event, we might ask questions such as “Is the event completed or ongoing?”, “Did it happen repeatedly?” or “Is it a single moment or a longer process?”

English rarely marks aspect explicitly, but consider:

- I will have eaten by 8 o’clock.

- I will be eating by 8 o’clock.

Although both events (the eating) take place in the future, we know that the first event has a fixed end point (is bounded) whereas the second does not. Another event could be habitual, for example in the sentence “I eat at 8 o’clock”. The meaning of this sentence is less clear without context, but one reading certainly is that the speaker regularly consumes food at this time of day. Enough background for now (before we get into lexical vs. grammatical aspect), let’s talk about probing.

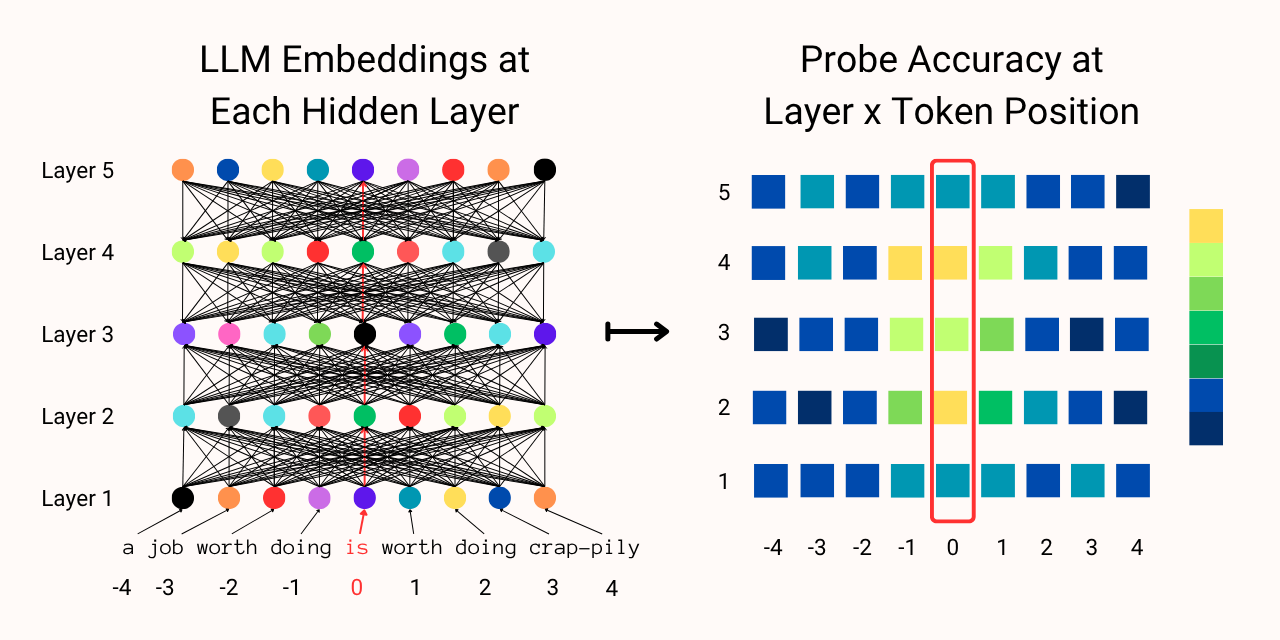

Probing is a fairly simple method for investigating the knowledge and behavior of neural networks. Supervised probes are nothing but classifiers that take some part of the LLM as input (in this case I’m looking at all the hidden layer outputs) to predict some phenomena as output (the aspect label). Continuing with the MRI metaphor, I’m scanning the LLM layer by layer, position by position, to identify where in the network aspect-related information might be encoded.

There are a few downsides to using a simple probing technique here. Firstly probes are models themselves, which means that a powerful enough probe will learn the correct labels from what is essentially noise. While this isn’t an issue for my experiment—since my end goal is to train an aspect classifier—rigorous studies on model knowledge will need a variety of controls to ensure that the probes are actually identifying information in the LLM.

Secondly, probing only demonstrates correlation, not causation. My classifiers can identify which layers and token positions produce embeddings that help predict aspect, but this doesn’t mean that LLMs inherently represent aspect in these places—or if they represent aspect at all. More powerful techniques exist, including the whole field of Mechanistic Interpretability, which is more akin to doing brain surgery rather than simple scans. One of my inspirations for this probing experiment was CausalGym, where researchers identified a bunch of syntactic computations that models perform. I couldn’t figure out a way to apply this method to identify aspect computation, but if you have ideas definitely let me know!

Now you’re thinking with probes

With all the background out of the way, let’s recap the investigation. We previously found that the LLM embeddings from the output layer aren’t good enough to predict aspect, so now we have to investigate whether or not LLMs capture good representations at all. We know from CausalGym and other research that LLMs process different parts of the sentence at different layers, so it’s possible that the intermediate layers are responsible for processing aspect information. To test this, we simply need to look at all the hidden layer outputs at all the embedding positions to find out if and where this is happening. Simple!

Problem 1: Natural language is diverse. Sentences can range from a few tokens to hundreds of tokens in length, contain no events or multiple interleaving events, and events themselves can comprise of a single or multiple tokens—or sometimes no tokens at all! As a practical workaround, I use the SitEnt dataset which comprises mostly single-event sentences, and simply probe for ±10 token positions from the event verb. I also remove any edge cases where the sentence has multiple events or the event verb doesn’t show up in the surface form of the sentence. Regardless of the number of tokens in the verb event, I always take the center position to be the first token in the verb. The final dataset allows me to train probes using the aspect label for the single event verb of each sentence, closing the loop for the experiment.

Problem 2: Aspect is distributed. Unlike syntactic features, aspect doesn’t have regularized forms—at least in English. Where CausalGym can investigate with minimal pairs (e.g. The authors are writing vs. The author is writing to test for number agreement), there is no simple way to change a sentence to guarantee a change in aspect. If I say I mowed the lawn, we would assume that the lawn has been mowed and the event has completed with a result. However, if I say I mowed the lawn for an hour, it’s likely that the lawn hasn’t been fully mowed and no result state has been reached. There is no simple way to tweak LLMs to investigate their inherent understanding of aspect, which is why I resort to simply probing for a signal that a representation could exist.

Problem 3: Unidirectional LLMs store data differently. With the success of GPT models, most LLMs mask later tokens for training purposes. This means that the later embeddings “see” earlier tokens when doing self-attention, but not vice-versa. While this is useful for generative purposes, my downstream task is to model aspect information, which theoretically performs better when all embeddings “see” each other. On the other hand, larger models capture richer representations of language and are likely to better understand aspect. I’m limited to sampling bidirectional models to get useful results for my downstream task; the largest I could find was ModernBERT.

Implementation Details

The experiment is fairly simple to execute, but there are a few details to note when replicating my methods. The full repository with instructions and documentation can be found here.

Making Experiment Data: The first task in this experiment is to extract hidden layer outputs from the selected LLM for all inputs and extract the correct token positions. I split this into two scripts, first extracting all outputs before selecting the embeddings that I want so that all embeddings are available in case I want to run additional experiments. As noted in problem 1, not all input sentences will have the same range of tokens, so I handle this by first searching through the tokens of each sentence to find valid positions within my desired range:

Show Code Block

# Load the data

df = pd.read_csv(infile, sep="\t")

df["label"] = df["label"].apply(lambda x: 1 if x == "DYNAMIC" else 0)

labels = df["label"].to_list()

texts = df["sentence"].to_list()

spans = df["start_char"].to_list()

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_name)

# For each input sentence, find valid token positions within range ±10

# from the first token in the verb.

input_indices = []

for i in range(len(texts)):

tokens = tokenizer(texts[i], return_tensors="pt")

center = tokens.char_to_token(spans[i])

indices = []

for j in range(21):

idx = center - 10 + j

if idx < 0 or idx >= tokens.input_ids.shape[1]:

continue

indices.append((j, idx))

input_indices.append(indices)

Once this is done I can simply pickle the tensors that I use for my experiment datasets. Generating embeddings this way allows me to both save memory and repeatedly use the same embeddings to check for any issues with later steps.

Custom Probes: It’s possible that aspect is represented non-linearly in BERT, which will not be found if we only investigate with linear classifiers. To keep my code modular, all probe objects should have the same input and output arguments as torch.nn.Linear:

Show Code Block

class MultiLinearProbe(Module):

def __init__(self, in_features, out_features):

super(MultiLinearProbe, self).__init__()

self.linear1 = Linear(in_features, in_features // 2)

self.linear2 = Linear(in_features // 2, out_features)

self.relu = ReLU()

def forward(self, x):

x = self.relu(self.linear1(x))

return self.linear2(x)

Memory Efficient Probing: The biggest issue I encountered was getting exploding gradients leading to classifiers full of nan tensors. After a ton of debugging, the likely culprit seems to be loading all the datasets and classifiers into memory together. Whether I trained on GPUs or Apple Silicon, I would immediately get unreasonable losses when I expanded my search to looking at multiple hidden layers. I’m probing 21 positions per input sentence, and since BERT-large has 24 hidden layers (25 including the input layer), that means 25 x 21 = 525 classifiers training on 525 datasets! Fortunately, I’ve already saved my experiment data formatted ready for use, so I simply need to load each dataset sequentially and erase my cache after each experiment:

Show Code Block

for layer in range(len(train_layers)):

train_position_paths = glob(f"{train_layers[layer]}/position*.pkl")

train_position_paths.sort(

key=lambda x: int(x.split("/")[-1].split("position")[1].split(".pkl")[0])

)

test_position_paths = glob(f"{test_layers[layer]}/position*.pkl")

test_position_paths.sort(

key=lambda x: int(x.split("/")[-1].split("position")[1].split(".pkl")[0])

)

for position in tqdm(

range(len(train_position_paths)),

desc=f"Layer {layer + 1}/{len(train_layers)}",

):

# Load pickled data here, pass into dataset and dataloader

labels, tensors = pickle.load(open(train_position_paths[position], "rb"))

ds = CustomDataset(labels, tensors, tensors[0].shape.numel())

train_dataloader = DataLoader(

ds,

batch_size=train_batch_size,

shuffle=train_shuffle,

)

classifier = probe(in_features=ds.hs_dim, out_features=2).to(device)

optimizer = torch.optim.SGD(

classifier.parameters(),

lr=learn_rate,

momentum=momentum,

)

for epoch in range(epochs):

classifier.train(mode=True)

loss = _train_one_epoch(classifier, optimizer, train_dataloader)

test_labels, test_tensors = pickle.load(

open(test_position_paths[position], "rb")

)

test_ds = CustomDataset(

test_labels, test_tensors, test_tensors[0].shape.numel()

)

test_dataloader = DataLoader(

test_ds,

batch_size=test_batch_size,

shuffle=False,

)

true, pred = _eval_one_epoch(classifier, test_dataloader)

acc = metrics.accuracy_score(true, pred)

macro_f1 = metrics.f1_score(true, pred, average="macro")

micro_f1 = metrics.f1_score(true, pred, average="micro")

results.append(

{

"hidden_layer": layer,

"token_position": position,

"accuracy": acc,

"macro_f1": macro_f1,

"micro_f1": micro_f1,

}

)

# Manually empty cache to prevent memory issues, persistent

# gradient issues will be due to learning_rate

if device == "mps":

torch.mps.empty_cache()

elif device == "cuda":

torch.cuda.empty_cache()

Results

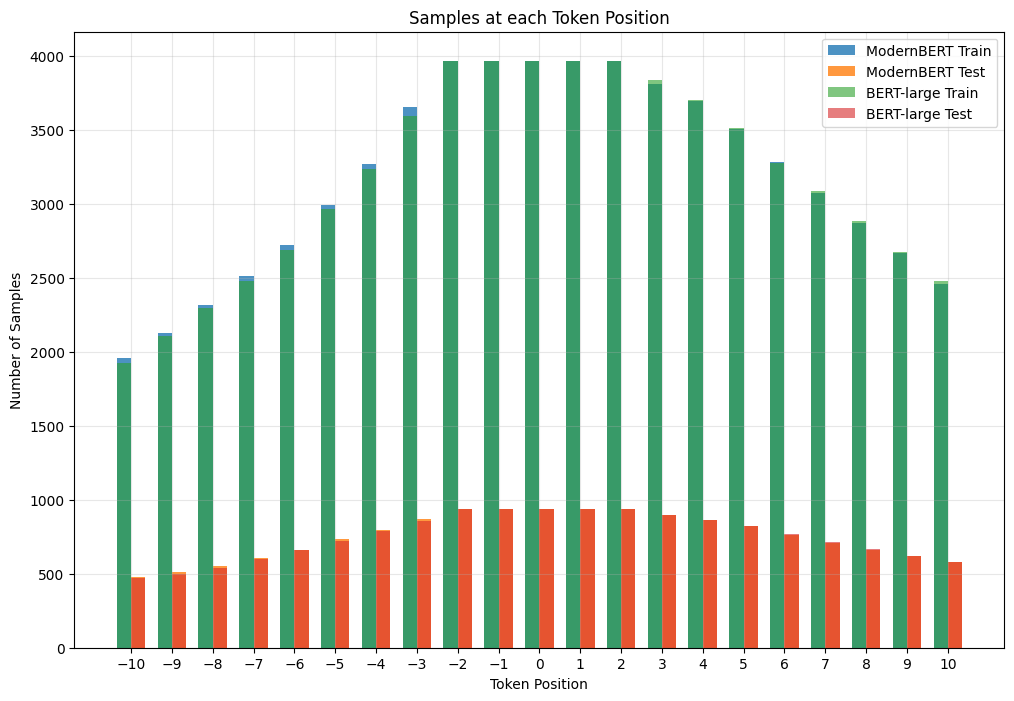

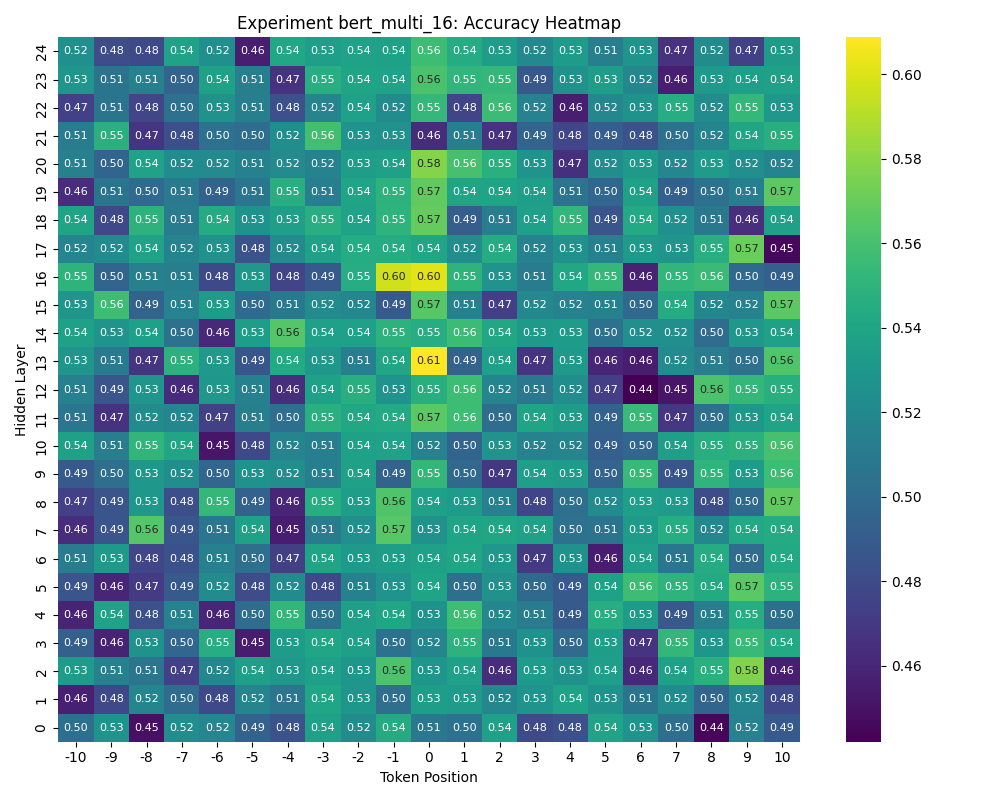

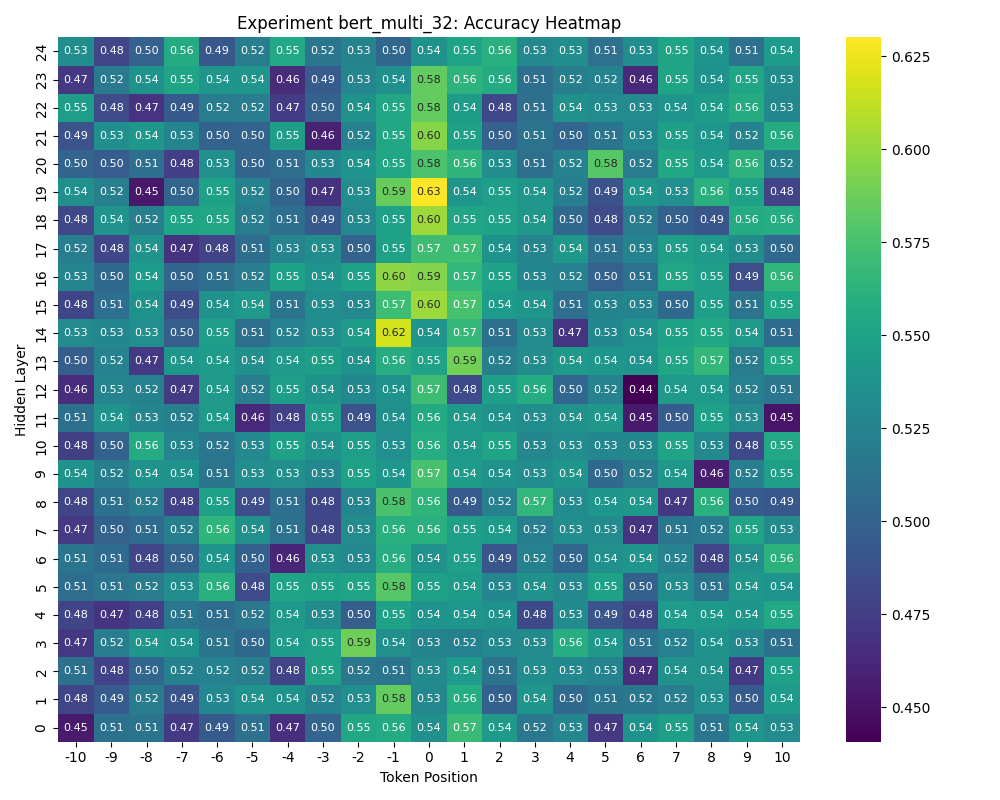

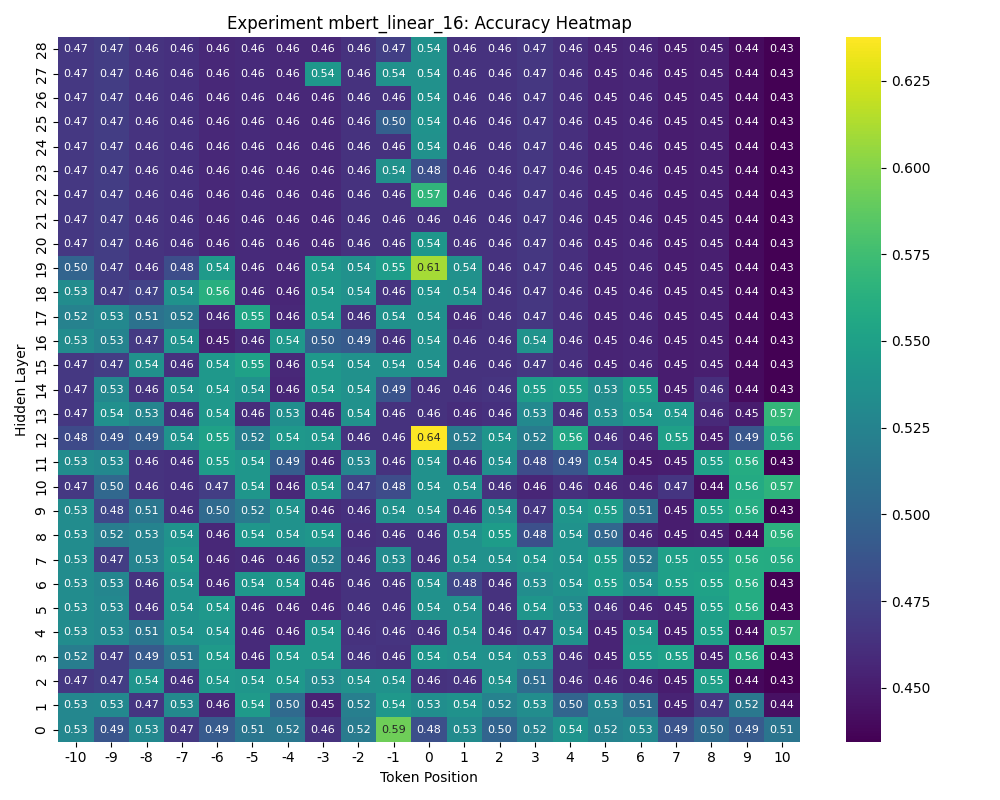

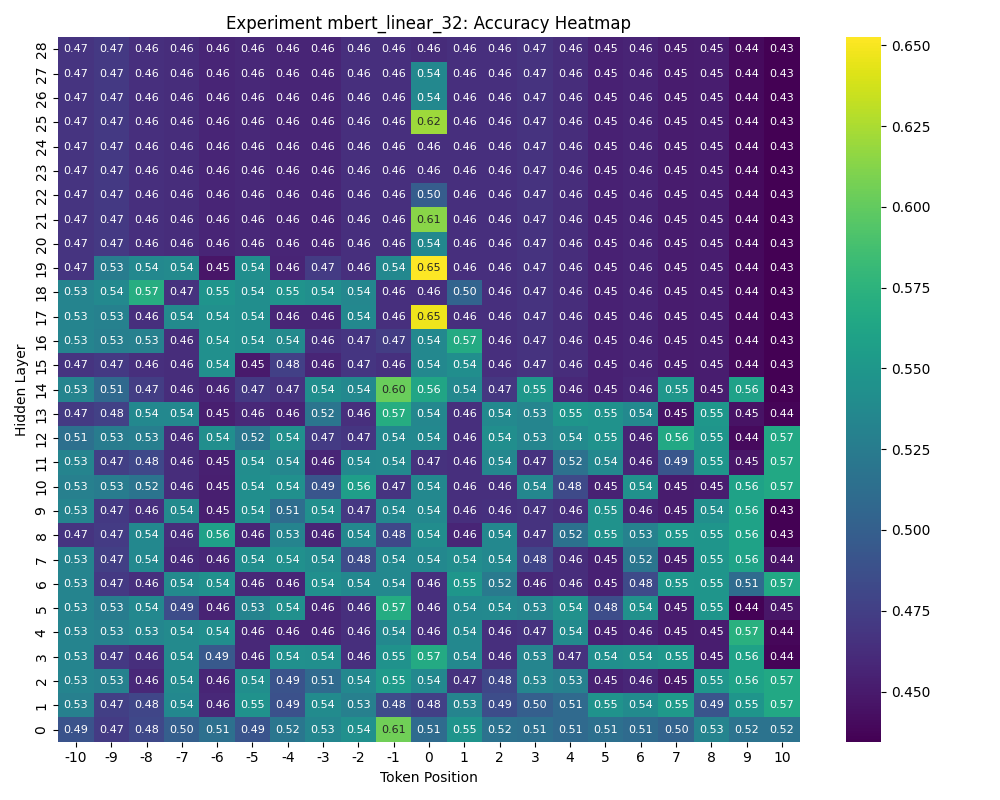

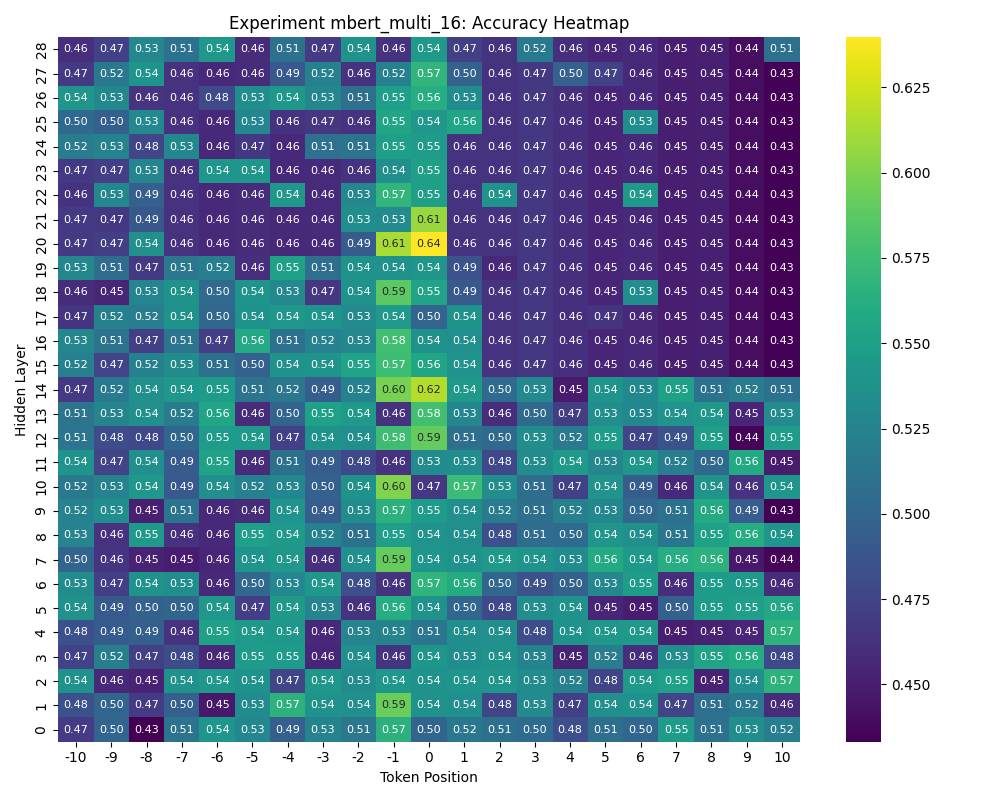

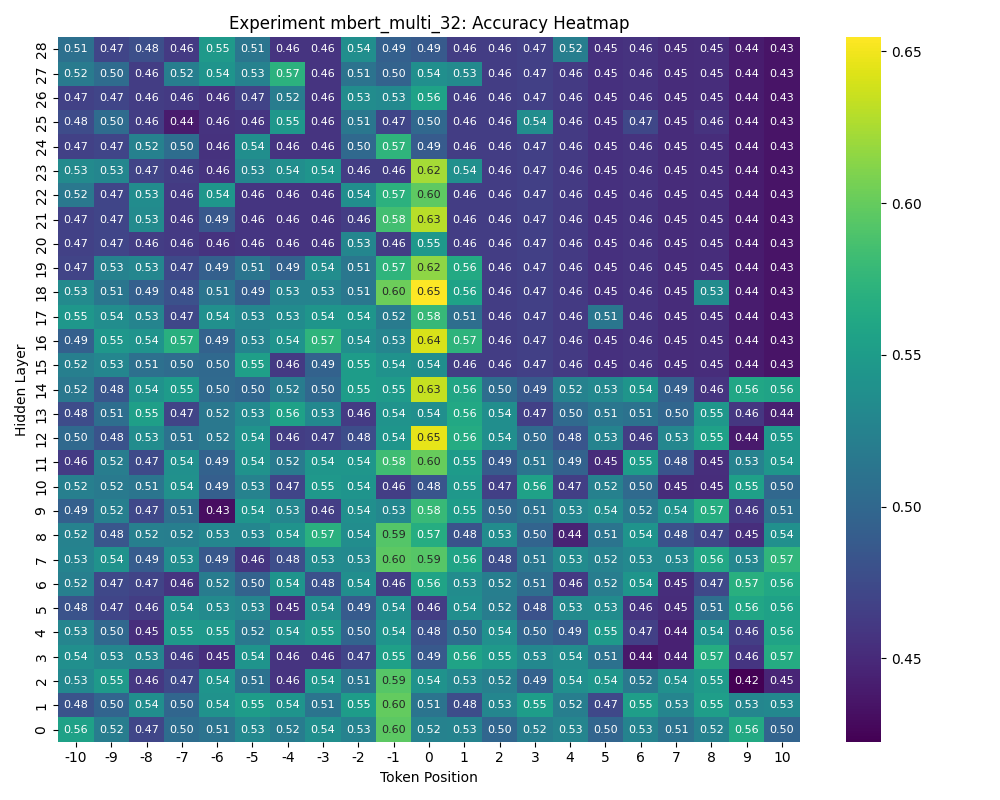

I tested BERT-large and ModernBERT on the SitEnt dataset, using both linear and non-linear probes (see above). The cleaned dataset is comprised of 3,967 train samples and 938 test samples with two aspect labels, Stative and Dynamic. Importantly, probes at different token positions will see different percentages of the dataset due to the variation in sentence length. Although this potentially biases the experiment, in practice this discrepancy doesn’t impact the overall findings:

Show Sample Distribution

Findings & Future Experiments

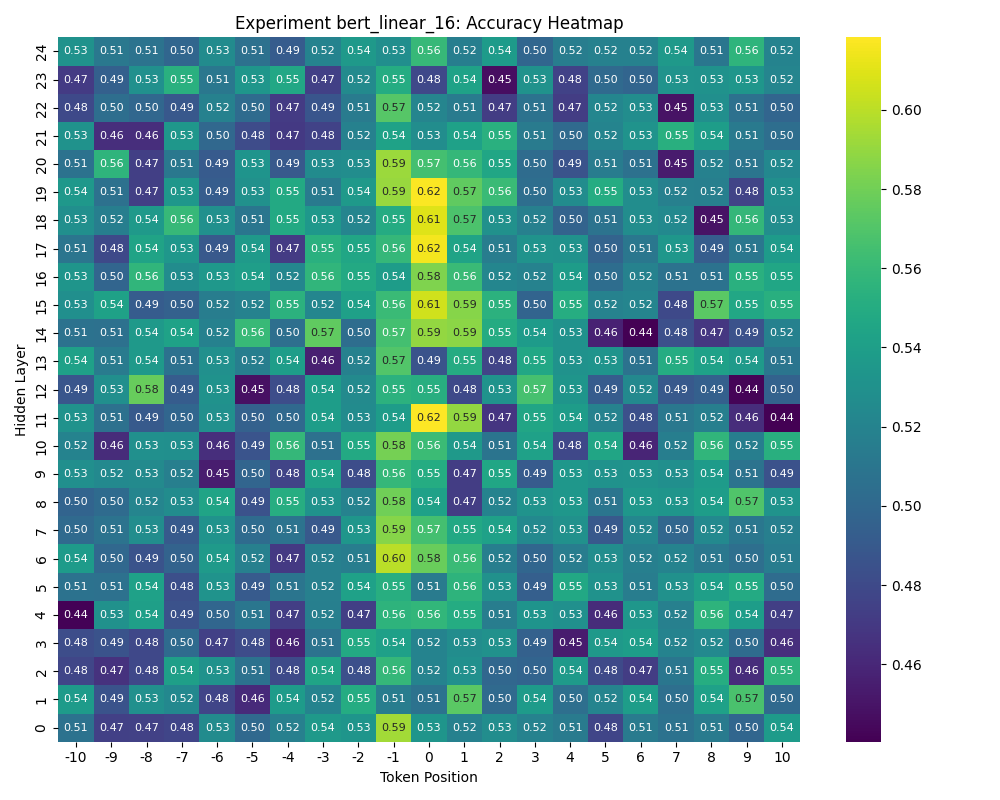

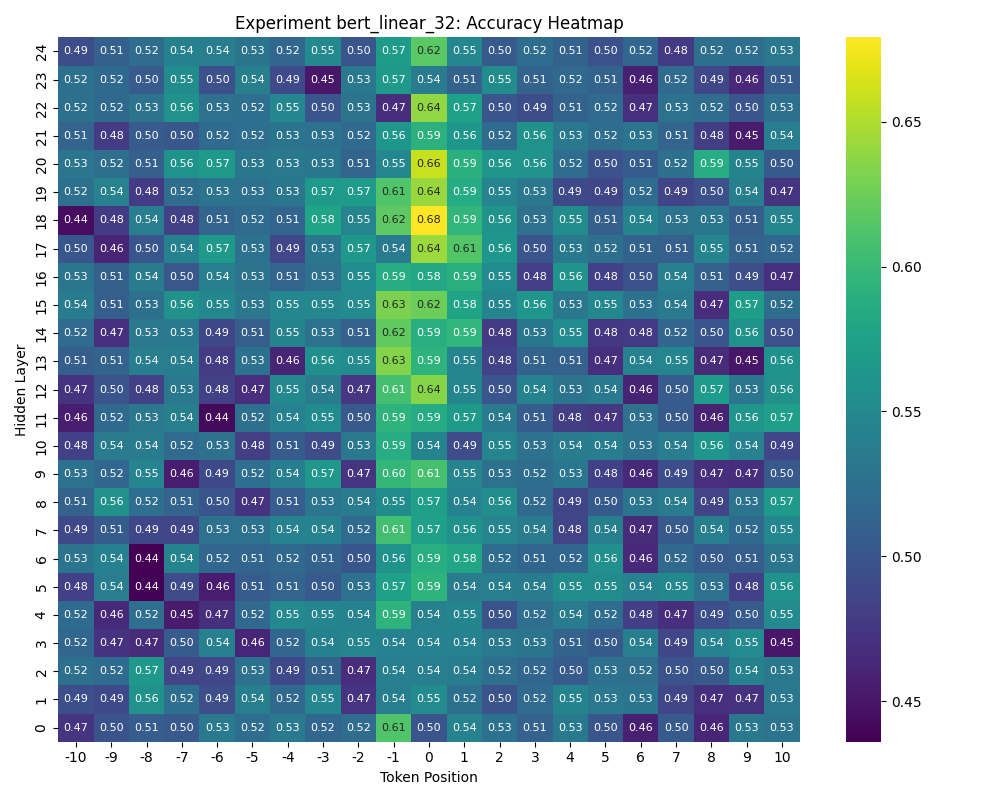

The results clearly demonstrate that certain token positions produce better aspect embeddings, even when the full dataset is available (from -2 to 2). No individual probe performs particularly well, but this is to be expected since each layer x position only represents a piece of the semantics. Across the board, the linear probes show the starkest contrast in performance for both token positions and hidden layers, suggesting that aspect is encoded linearly. The ModernBERT results contain regions of identically poor accuracies, but this is due to exploding gradients breaking probe weights. Two findings in particular are surprising and warrant further investigation:

Finding 1: Aspect is strongly correlated with the token before the verb

Although we expect the verb token to capture the best representation, the embeddings in the -1 position also performs quite well. In fact, the -1 position often performs better than the +1 position, even though the +1 position is sometimes part of the verb! This suggests that the model stores a part of the semantics in neighboring positions and needs to be accounted for when using individual embeddings. The fact that the phenomenon is more pronounced at higher epochs strengthens this finding and warrants further study. When looking at other LLM phenomena, it’s useful to investigate fuzzily by looking at neighboring or tangentially related embeddings where models may unintuitively encode information.

Finding 2: Intermediate hidden layers seem to capture better representations

Moreover, probes trained on outputs at the input layer (layer 0) and the output layer show less variance across token positions. This finding strengthens my hypothesis that aspect semantics is being processed within the model but becomes less important for the output layer, and explains why results from my previous exploration performed poorly. Confoundingly, which layer produces the best representation varies across experiments (including ones not shown here). Without further investigation, it’s difficult to select which layer output to use for downstream tasks. Interestingly, for a few of the experiments the probe at the -1 position in the input layer also produces strong results, sometimes better than the probe at the 0 position in the output layer. One possibility is that the -1 token is strongly correlated with a part of speech that impacts the meaning of the verb.

Next Steps: Fuzzily probe models by semantic roles

Based on these two findings, I can verify that LLMs capture useful representations for predicting aspect located near the verb token. However, only the verb token position is linked to a part of speech while other positions are somewhat arbitrary. The next investigation should instead group hidden layer outputs based on semantic roles, keeping in mind that neighboring positions might also encode some of the desired information.I would also be able to test sentences with multiple event verbs, since parsers generally assign roles to a target verb. The results of this experiment could paint a more complete picture of aspect representation in LLMs, especially if different layers produce better probes for each semantic role.

Takeaways for your probing experiments

- Hypothesize about model behavior by thinking about how humans conceptualize information to focus your lens. If I didn’t think about verb positions, my data would not look clear at all.

- Find the easiest experiment to run and investigate iteratively. Verifying my hypotheses about intermediate layers and token positions ensures that helped me find the next place to look.

- Run multiple versions of the same experiment: probing is an art, not a science. I wouldn’t have figured out my gradient issue if I just had one heatmap to look at and probably would have concluded that BERT doesn’t capture aspect.

- Sometimes features are non-linear, so it’s always smart to test with different types of probes. However, if your probes get too complex you should benchmark with randomized data to ensure that your findings are real.